After a busy couple of days where there really wasn’t any time to sit down and play the guitar in any kind of meaningful or thoughtful manner, I sat down today to return to this strange world of triadic voice leading. A couple of things are slowly dawning on me: while playing the triads horizontally as a chord exercise is useful as an exercise, that’s about where it ends. Most of the interesting things I’ve come up with have been melodic, and therefore if I’m ever going to improvise using these kinds of sounds, it will probably happen only by becoming very strong in each position and then eventually being able to combine the positions fluidly, much like what we all go through when we learn them all in the first place.

This reminds me of a story a Rabbi told me. According to him (certainly not to me), each day of the Jewish calendar (lunar, not solar) has a certain energy to it. Every time we come back upon that day of the calendar, this same energy fills us every time. He said: imagine not a circle, because time is always moving forward, but a spiral. This reminds me of diagrams trying to explain four dimensional space-time. The same way 2D becomes 3D with the introduction of depth, we are literally time travelers, traveling through space AND time. Anyhow, to get back to the Rabbi. This idea of constantly moving forward while at the same time constantly returning is very powerful and relevant to the musical journey we all take.

As I often say to my younger students: think of this as a video game. The best video game there is because you only have to buy it once and it never ends and people might even pay you to watch you play or have you show them because it comes with a million different manuals and most of them, like this one, aren’t very good. As you progress through the levels, the structure remains the same. You have to jump over cliffs, fight bad guys, solve puzzles, whatever. This cycle of actions never changes, but becomes more complex and sophisticated as you play through the levels.

So imagine you open up a guitar book, or go for a lesson, maybe you’d been playing by ear, learning from the internet, playing songs, and then all of a sudden somebody points out to you that there are a finite number of patterns that describe everything you’d been doing up until this point. These patterns are the positions. You think to yourself, boy, I wish I knew all of these really well. I wish I could play all sorts of neat stuff in all of them, and maybe even zip through a few of them, link them together fluidly, see what happens if I get stuck kind of in the middle of them, etc. So you get to work, playing up and down all the positions. Once you’re feeling confident and/or bored and/or too excited to wait, you decide that now you’re going to pick two positions and work on doing things that seem to connect both of them. Then you repeat this for all the different positions (although you probably don’t like some of them and in all honesty almost never use them...).

Maybe you buy a book that has to do more with metal kinds of playing where the more notes per string the merrier. Maybe inside this book, there is a section that deals with playing each mode, but rather than saying you’re in closed position, you always start on your first finger and then play 3 notes per string (advantages to metal-heads should be obvious). Maybe you realize, you’re playing a sort of hybrid scale POSITION that seems to fall in Dorian and Phrygian. Maybe you also start to realize the wonderful phrasing possibilities when you have more notes per string, or get used to playing them with different fingerings. Maybe you start to see the position in terms of notes, and after a while you could play through all the modes using only your first finger because your understanding of them musically is deep enough and your technique effortless enough and your concentration solid enough that this simply doesn’t seem challenging anymore. Maybe you opened up Mick Goodrick’sAdvancing Guitarist and decided to spend serious amounts of time playing on a single string, forcing yourself to think melodically, and to internalize the harmony on a level deeper than this shape during that bar. Then maybe after a while you seem to be doing any or all of these at the same time.

In other words, maybe a few years have gone by since somebody explained to you what modes and positions were and you’ve worked very hard on them. You have gone through a whole process of learning a vocabulary, learning to navigate your way through that vocabulary, learning to tastefully and effectively use that vocabulary within various musical contexts, and finally developed such a thoughtless and intuitive grasp of this vocabulary that you can actually think about other things, such as thematic development, while using this vocabulary. Congratulations. But just like Monopoly, this game goes in circles and never ends. Except now you’re much richer.

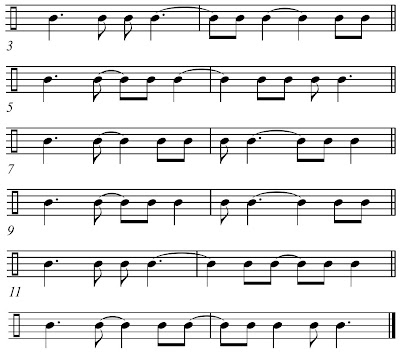

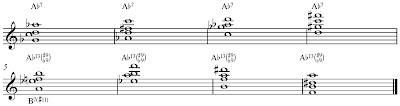

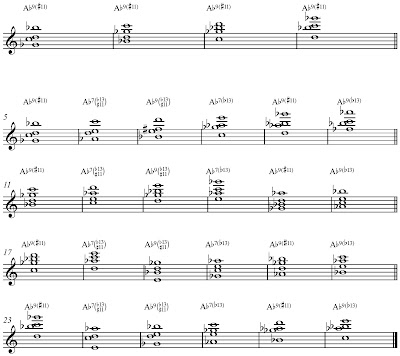

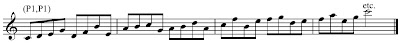

So to get back to triads, the more I play the longer I feel this is going to take. I could spend months in just one or two positions (Major and Lydian). The possibilities are massive. Today I discovered some licks which do a couple of different things that in themselves require some dedicated time, once I actually know the exercises better anyways. For instance, alternating the direction of the arpeggios (one goes up one goes down one is totally broken and any combination of any of these in any spot as in bar 1). Also adding in lots of passing tones, creating something which might not seem all that triadic but in fact is based on a series of triadic voiceleading (bar 8). Something that is not all that triadic at all but is starting to use intervals in ways I couldn’t really have done before all this (bar 5), using common tones as pivots between two different triads in a smooth and speedy fashion (bar 3). The possibilities are endless and this is all just in one position.

Mick Goodrick says that he’d love to imagine a guitar player who spent their whole life playing since the age of 4 in only open position. He’d have a range 2 octaves plus a 3rd and he would only have one doubled note (B). He could rip through giant steps and comp like a champion. What the hell would that look and sound like? Maybe it’s never going to happen because nobody who picks up a guitar has that much self restraint. But the point he’s making, at least I think, is that the musical possibilities on a guitar within one position, mathematically speaking, are endless. If you forced yourself to spend a very long time limiting yourself so drastically, what sort of possibilities might you eventually come up with that no one had thought of up until that point? And if you start taking this seriously, who needs 7 positions if they’re under the age of 40?

This process of learning continually repeats itself at an ever increasing level of sophistication. We are constantly faced with new ideas which we learn to integrate in the exact same manner and following the exact same stages (although it’s really not that clear cut). Rather than days of the lunar year with energy (remember the Rabbi), this metaphor of the upwards spiral seems to speak to me about what it means to practice and learn new things. To constantly undergo the same process, and yet it is different each time BECAUSE of time, because we’ve evolved as players.