Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Rhythmic Jigsaw Puzzle

A combination of different inspirations has led me to a very specific rhythmic problem. I’ve been listening to a lot of recently composed classical music which is influenced by Indian rhythms. There is a lot of polyrhythms, of long beat cycles etc. One thing I’ve noticed is that typically we see the play of 8th notes grouped into 2s and 3s, we see triplets, and duplets, and we see things like a rhythmic pattern consisting of an odd number of subdivisions superimposed over another rhythmic figure consisting of an even number of subdivisions, causing one to feel displaced.

All these things are great compositional and improvisational tools, but they will serve us another purpose here. It’s hard sometimes to go into double time. But what about triple time? Mitch Haupers showed me a very useful exercise that involved a section of his book Factorial Rhythms dealing with rhythms in 6/4.

Using a metronome play what is written with the click representing the quarter note. Continue on to playing the 6/4 rhythm again with the click playing the half note. And then the third time the click will represent the dotted half note (triple time). This poses some interesting problems because the same rhythm may sound at one speed as 2 groups of 3 and at another speed as 3 groups of 2 which makes this especially disorienting.

Of course, it should be obvious in hindsight why Mitch very wisely chose to expose us to this kind of exercise using 6/4 rhythms. Look at how beautifully the rhythm fits into all 3 times. If he’d started with what I’m about to show you next, it would have been a little too much (hint).

What I’ve been seeing a lot of in the repertoire I’ve been studying and that seems like a natural extension of this exercise, is how to play 3/4 rhythms in the span of 2 or 4 beats,. What I haven’t been seeing is the MUCH harder problem of how to play 4/4 rhythms in the span of 3 beats.

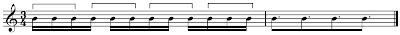

Let’s start with 3 over 2 or 4. The division is actually quite simple. To divide 2 beats into 3 is a quarter note triplet. But to understand them more precisely we need 8th note triplets.

Now here’s where the real problem starts. These rhythms in themselves are easy enough to play with a bit of practice, but now we’re talking about superimposing rhythms over other rhythms. So let’s look at the tuplet as a structure over which we can hang a new pattern. This is going to become a more complicated polyrhythm because it is going to involve a full blown metric modulation superimposed over the original rhythm.

Let’s take putting 4 over 3 like I said we would. We need to divide the 3 beats into 16th notes, and then group those into 3s.

Now we get into a problem which could arise with the previous examples as well, come to think of it. As you can see, to superimpose 4 quarters in the space of 3 results in 4 dotted 8th notes. But what now if we wish to play a measure of 4/4 over a bar of 3/4. yikes! Now we’re going to have to have to use dotted 16th notes to represent the 8th note from the bar of 4/4.

The trouble, whether you try and think it through to exact mathematical values, or just feel your way through, is how to take something which you’re feeling as a natural division of 3 (such as the dotted 8th) and play a duplet over it (the dotted 16th). Now you have duplets which completely obscure where the original beat used to be, which is why we’re forced to write things out as they are in the middle of the 3 bars below.

It feels like we’re playing duplets in 12/8, and then superimposing THAT over 3/4. Ouch.

Friday, August 14, 2009

Staying Flexible

After looking back at everything I’ve written in the past 8 weeks or so, I’ve come to realize something: I’m not very good at sticking to an agenda. When I first sat down to create an agenda for the future based on the ideas from the Goodchord workshop, I had decided to focus on triads for a year, thinking horizontally, thinking in terms of a bunch of independent chord shapes, thinking harmonically. Very quickly though my interest became melodic, became vertical, and my mind began to wander into other territory harmonically. I still I think I can spend at least a year working on triads. After nearly two months, I can do the 4 patterns on only two modes out of the minimum of 10 or 12 I’ll need to learn them in for practical purposes. But I’m not where I set out to be. And that’s a great thing.

It’s happened to me when using the reference material of other authors and teachers that one of their ideas might inspire a concept or sound for me to pursue that was only indirectly related to their material. But I find this especially interesting now, as I try to create a body of reference material and interact with it as a practicing musician simultaneously.

Setting out to do one thing and accomplishing another is one of the beautiful things about playing music and one of the reasons we should never stop discovering things and growing as we practice. It was a nice idea to think of a hundred different variations on the triad exercise, or the nested serial intervallic sequences or whatever you want to call them (see “Oh Boy...” or “Spread it Around a.k.a. Serial Soloing”), but what good would it actually do me or anybody else reading those ideas to get totally bogged down in them and let them eclipse the kind of creative and fruitful, discovery oriented practice that we can and should all be doing more of. In five years, when I’ve mastered the triads and can play them to pieces and am looking for a warm up exercise that can also be a brainteaser, then maybe I’ll go back and look at some of that stuff. But in the meantime, the best thing I can do is to let go of that material, and not feel compelled or committed to sticking with it, even though I made it up with every intention of doing so.

And as for the horizontal triads, it turns out I don’t really even like them all that much (right now, at least), so why allow stubbornness to stifle me? In the end of the day, music should be an enjoyable activity and you don’t win any points for being right or wrong. I think we get preoccupied with being able to do things that are supposed to be really hard and being better than other people (you know it happens sometimes, it’s okay), instead of being focused on being creative and connecting with others in a meaningful way.

So let loose, don’t be stubborn, let the music flow, commit to the material that ignites your passion (tough luck if it happens to be material that takes a lot of prep-work) and don’t be afraid to change directions, keep it simple, be “bad” according to the person with the self-inflated ego trying to label you, and stay true to yourself.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

A Page From Mr. Goodchord

What do you do when you’ve discovered a new voicing you like? Well says Mick Goodrick, see if you can transpose it into the other modes of the scale. Lately I’ve been dealing with diminished and whole tone chords because these chords transpose very simply seeing as the fingerings don’t change.

What I have just come to realize, although it was right in front of my face the whole time in Mick Goodrick’s Voice-Leading Almanacs, was that like the diatonic D2&4 voicings in the major scale, all the voicings discussed previously can be converted into D2&3 and D2&4 with quite amazing results.

Monday, August 3, 2009

Sunday, August 2, 2009

Examples of Drop 2&4

Some nice drop 2&4 lines. Inspired by a chart by Mick Goodrick which lists all the different possible chords derived modally to play over the II V using melodic minor. (For more info on what different kind of chords there are check out the Voice-Leading Almanac.