Saturday, December 19, 2009

Why Do?

Wednesday, December 16, 2009

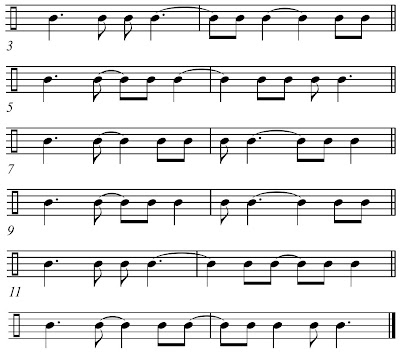

Fun Clusters With Open Strings

The 5th bar is the most interesting shape to try and find a picking pattern for because there are two separate sets of strings where the note on the higher string is the lower sounding one.

Tuesday, December 15, 2009

Monday, December 14, 2009

The Song Remains The Same/The Return Of The Almighty Triad/Wish You Were Here

With that said, I find it strange that most beginning jazz students are introduced to the art of improvisation at the same time they are introduced to the vocabulary of jazz, which happens to be more complicated than some other available vocabularies. As I mentioned in my last article, I discuss with student’s in the context of simple songs, triadic in nature with slow moving harmonic progressions, or even pedals, how to create a complex interaction between the different components of music (i.e. using multiple skills at the same time). This might mean playing a continuous melody which involves two or three closed positions and transitioning between them using the skill of playing on one string. This might involve working triadic arpeggios or chordal gestures into our melodic playing or embellishing triads using the knowledge we have acquired through the playing on one string or in closed position. This whole idea of synthesizing concepts which were originally introduced as separate and unrelated lies at the heart of improvisation, in my opinion. If a young student can master complex ideas with a simple vocabulary, to extend these ideas to a more complicated vocabulary will come much more naturally to them. Why are they trying to solo using fourths or chord substitutions or drop 2 voicings if they can’t even solo using triads?

The study that follows serves two purposes for two different skill levels. The first group is the maturing student who I was just describing. They will be pushed to analyze the piece and name all the notes on the neck of the guitar and in doing so they will build stronger fundamentals and have an easier time playing closed positions triads. Although they probably will never play open triads anytime soon, it will be a good exercise to help them with their closed triads. For this reason, tabs have been included.

Oh, I forgot. This exercise is about open triads. A sound which I find very interesting and particularly beautiful on the lower five strings of the guitar. I have already spent much time exploring the possibilities of triads in this blog as either vehicles for melodic inventions or chord substitutions. Perhaps in working on open triads I might unlock new possibilities in both these areas. And just like my students, I think it would be good to start with something simple just to get started. Naturally, since this exercise is much less mind-blowing for an advanced jazz musician than a young and inexperienced rock musician, it should be transposed into all twelve keys.

Friday, December 11, 2009

The Big Jug and the Little Jug

Contrary to what some might say, the answer would be no to all those questions. There are a couple of reasons for teaching this way.

The first and most important principle is that a teacher’s job should be to help a student find their voice and understand that this is going to differ from their own voice. With that said, one way to help a student make the decisions which will shape their personality and playing style is to over-inform them. What they are forced to do is to edit the information you provide them and choose to focus on what is important to them and what resonates with them. If I tell a student to work on four things knowing they will only work on one or two of them very well, what I learn the next week is which thing is of the most interest to them and this helps me focus on what they need. They’ve made a selection without being conscious of the fact that they were offered a choice. The student thinks that they have failed to complete all their tasks but that was never the point. The question was not whether they would succeed but how they would choose to fail.

This is the first level of over-information. Once we have discovered and begun to pursue a specific thread in the student's development and found something specific to work on for a given period of time (perhaps two to three weeks of intense focus, always good to change the subject within a month), the next level of over-information begins.

Here’s an example. I might telling the student to work on playing scales in five keys horizontally on a single string, to practice all seven modes in closed position, to work on combining triads with the pentatonic scale to develop cool rhythmic gestures, and to be able to improvise competently on a simple progression (think Wish You Here Here) using all these techniques and combining and interchanging them fluidly. In a week. Even though I know that what I’m asking for is simply not something that happens in a week. But what are they going to do that week and when they come back what will they be playing? What will have been worked more on? What will have been overlooked or considered to be a dead-end? Where did they see the possibilities? And from there we can then dive into the topic of their (unconscious) choice in greater detail and begin the process of over-stimulation again. Suppose they seem to be interested in single string scales. Not only should you do five keys, but practice playing thirds and sixths on all available combinations of strings trying to understand them as either harmonic progressions or as doing the one string exercise but on two strings at the same time. Once you can feel their creativity turning stale and their interest beginning to wane over the following weeks you can slowly pull their focus back to a more global perspective of all the different areas, and then bombard them with the same assignment again and see what they come up with the next time. Maybe they will be interested in triads. Come up with some unbelievably ridiculous task involving triads to be completed in a week and see what they do. This allows them to mould their own voice. You simply point them in a direction and see if they walk there. If they decide to walk somewhere else that is also fine. Whether they choose to follow or not, they are reacting to your guidance and you have positively affected them.

Name a subject and there will be a million things to try, a million different exercises to work, too much for any human being to do. There is always a next level within each little tiny nook of technique and then there is the combination of all techniques which is itself a never ending technique. So we have to choose. Allow the student to make the choices for themselves. Present them with options.

Mick Goodrick talks about the Chinese food menu approach to practicing. Write down all the different things you can work on and then every day pick out an item or two (like ordering from a menu). The menu of practicing and the menu of music period is endless and infinite. You could eat the same meal every day or try something new every day or build up a network of dishes you like and maybe try a different one when you’re feeling adventurous. That’s gone far enough and you get the point. Present students with a menu of their own and allow them to pick their own dishes. Don’t be like an obnoxious parent and tell them what to order.

Finally, we get to the jugs. We have a big jug in the back of our heads and a small jug in front. You, as a teacher, are holding the jug in the back of your brain, which, having more experience, is much fuller than the jug in the back of your student’s brain. Every lesson you pour your entire jug over your student and they catch whatever they can in their small jug. The small jug passes this on to the big jug, and probably spills some stuff along the way. The next lesson you return and poor the whole jug over the student and again they catch what they can in the smaller jug. And again they transfer to the larger jug, which is very slowly getting fuller and again they lose some water along the way. This is the transfer of knowledge.

Even when we teach ourselves, we have to understand this about our capacity to understand. We run to the well of knowledge and become greedy for information. We sometimes ignore the fact that our little jugs are full and continue to poor water into it, watching it overflow but desperately refusing to admit it. We need to stop and allow the little jug to carry itself back to the big jug. We are only wasting our energy. We all know what it feels like to reach the point in our practice when we have gone too long and start to get worse instead of better. We must respect the process of learning, of deep learning, and understand that our little jugs are only so big, not to become too concerned with filling our big jugs. Because there is simply no rushing this process.

So failure is a beautiful and necessary part of learning. As we acquire skills, we must understand that what we seek to learn is most probably massively huge and could never fit in our small jugs. So we must be patient in the way that we practice and adjust our expectations about our results. We must recognize that some things cannot be learned in a single session, that they are a process which takes time and therefore are pointless to rush. And we must embrace failure as an important part of transmitting information because the best way to help a student flourish involves designing tasks for them which they absolutely cannot complete. We must accept and enjoy their failures with mutually felt humour and lightheartedness. The point is exactly not to get things right the first time. The point is to fill up one jug at a time and not be afraid to spill a bit.

Tuesday, November 24, 2009

Monday, November 16, 2009

Dynamic Duo

Two interesting articles on the subject include http://www.kylegann.com/notation.html, which talks about the dangers of over notation, as well as http://thebadplus.typepad.com/dothemath/2009/09/interview-with-keith-jarrett.html, an interview where Keith Jarrett talks a lot about touch, about a lack of sensitivity amongst jazz pianists and I would like to extend his point to many jazz guitarists.

Horn players spend their formative years learning proper technique and reading music with a focus on how to play and phrase and feel it accurately. Most guitarists probably learned music other than jazz and in some combination of reading magazines or books and piecing things together by ear. When we are introduced to jazz, we are presented with lead sheets, sparse papers with little information on them other than the most essential to get a musician started on the process of interpretation. It is still necessary to listen to performances of the song, understand all the harmonic nuance that every good jazz musician brings to a tune, that the changes as they are written are a starting point and should never be considered a destination and that any good group contains both a rhythm section and soloists who are open and flexible enough to go places other than the typical. Back to the point, guitarists encounter a written form of jazz which does very little justice to the actual performance of jazz. There is so much nuance in any good jazz musician’s tone and use of dynamics, their touch on their instrument, and yet so little time is devoted to developing this consciously with students of jazz. You got it or not, I suppose. Actually, I don’t suppose that at all.

When I started taking guitar lessons formally in school, my wonderful teacher Nick Ditomaso never failed to amaze me week after week. It seemed like there were a million things he knew how to do and I just didn’t have a clue what any of them where. This changed about halfway through our association. Over a year and a half I’d worked furiously to learn all the scales and how to improvise and comp using drop 2 chords and a generally more melodic approach to rhythm playing. As my second year came to a close, I’d succeeded in doing this to some degree. I’d even figured out a couple of voicings that seemed to be all mine. But I still didn’t sound half as good as Nick did.

Now I began to become truly awestruck in a much deeper sense by Nick’s sound. I couldn’t understand how he sounded so amazing and I didn’t. When I watched his hand move, I could finally recognized the voicings and patterns. I’d learned a decent chunk of the standard jazz vocabulary on my instrument (in terms of scales and voicings), and like any other guitarist playing standards, Nick was often referring to this vocabulary in his playing in ways that I could comprehend. But still his sound was lightyears ahead of mine and I didn’t really get why.

Over the next year and a half, I began to bridge the gap in our sounds but never consciously and only very minutely. Nick always told me to work more on my tone but I always felt like what he was really asking me to do was buy a new guitar and that wasn’t going to happen. I wasn’t ready to understand what I was missing because I was still too focused on vocabulary. I was fascinated with the idea of altering chords, of playing outside, using chromatic passages, learning tunes and finding voicings which allowed me to play the harmony and melody at the same time. I loved Lenny Breau and Ted Greene but no matter what chords I learned I could never even begin to approach their sound. As I got my hands on all the material I could about them and by them, I was again, much like with Nick, chronically disappointed by the lack of a secret chord or two which would let me sound like them.

Then I met Mick Goodrick. Mick talked very little about touch. But he played in front of me every day for five days and in just sitting and listening to him over the course of a week it hit me. Watching him play, hearing him attack, hearing his careful attention to dynamics and his quiet authority had a big influence on me. When I met him for my lesson I was determined not to try to impress him by overplaying. How many people walk into a room with Mick Goodrick and whip out their best licks in the first chorus of their first solo and accomplish nothing musically and tell no story whatsoever? We played Stella By Starlight and I came in very quietly and delicately. I tried to be melodic, didn’t worry about conveying to Mick that I knew the changes and could play over them. I wanted to build something because I thought that would be more impressive and so accordingly I wasn’t in a rush. Along came my second chorus and I started to lay into the notes a bit more. This is the first time in my life playing jazz that I can remember where I consciously used dynamics as a major factor in the building of my solo. But I went too far too fast. It was too loud for Mick. I’d spoiled our sound with a lack of sensitivity and he stopped me and told me so.

The same day I played a free jazz piece with 3 other guitarists, and 2 very talented and wise musicians named Vardan Ovsepian on piano and Bob Weiner on drums. Minutes into the piece, it still felt like it wasn’t building to me, like the other guitarists were holding back too much or too scared to play with commitment so I took it, quite arrogantly and mistakenly, upon myself to push things in a certain direction. Quite naturally, I once again got very loud very fast. What resulted wasn’t so bad, but it was basically musical premature ejaculation. Things boiled up very fast and cooled off almost instantly after hitting a peak. It was a noisy experience. And I experienced a sensation of extreme heat while playing which left me overwhelmed and flustered and actually drove me to tears a bit later in the day.

To say I came home and went wild about dynamics would be a lie. My first blog entry was a summary of everything I’d taken away from my week with the Mr. Goodchord team and there is no mention of dynamics in that article, nor did I mention either of those very important stories. I was overwhelmed by these events and I wasn’t ready to face them yet. But they were a part of me and they were guiding me. I was scarred and quite unconsciously the way I heard myself began to evolve. When I finally recorded myself almost 5 months later (you can hear that recording of Stella on MySpace), I was pleased to finally hear what I’d been searching for without knowing it for four years: dynamic nuance. Even my most stock phrases, things I’d been playing for most of those four years, suddenly were popping out at me. They had become three dimensional. My foot was in the door.

Can we work on these things consciously? Can we build exercises to help us develop the physical skill of having many different and interchangeable levels of attack?

Here are a few:

Take any ii-V lick and try playing it at a single tempo and see how many different volume levels you can achieve. Try this at different tempos and see which volumes are difficult. The faster you get, the more obviously hard it becomes to play quietly.

Another thing to do is to play a scale up and down at various tempos, placing the accent on a different 16th note every time (1). Also, this can be done with 3 and 5 which displaces the accent (2).

Also, as we get higher we have a tendency to get louder and play harder and there’s something inherently more relaxing and gravitational about playing a descending scale. So try playing a scale getting quieter going up and louder going down (3).

This conversation does not only apply to playing single notes with a pick. Using your fingers to play chord solo types of sounds is infinitely more effective in terms of dynamics as well. I think my studies are actually very good for this exercise. If you see the videos, you’ll notice that I arpeggiate the chords, perhaps add in melodic embellishments, but that none of this was notated. Playing the studies is firstly a very note oriented exercise in learning new and wider voicings. But unconsciously, I was also working on popping out the melody from the overall texture of the rest of the chord, by creating dynamic contrast between the most important note at any given time and all the others (it's hard to tell since the audio quality is so garbage). These studies are good for that because the wide voicings tend to make the melody notes sound more isolated, which can help you start to hear things differently. I think they did that for me.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

The Beethoven Blessing

Beethoven started going deaf around the age of 30. In his wikipedia article it states that “Over time, his hearing loss became profound: there is a well-attested story that, at the end of the premiere of his Ninth Symphony, he had to be turned around to see the tumultuous applause of the audience; hearing nothing, he began to weep.” Beethoven’s last and unsuccessful attempt at performing his own work was in 1811, sixteen years before his death. So how did a man so profoundly deaf continue to compose new and influential pieces of music for 16 years, especially his ninth symphony and and the late string quartets?

Well, go back to his very first string quartets and you’ll find the exact same harmonic language. In fact, check out his symphonies or piano sonatas, everywhere the same chords follow the same sequences. So what was on Beethoven’s mind?

I would like to hypothesize: everything else. Notes are the most insignificant aspect of music. You either follow the principles and standards of a style or not, and therefore sound one way or another. This takes time to understand and be able to employ, certainly if you have an interest in numerous styles all with different aesthetic principles (or lack thereof) as well as general attitudes and emotional demands. Although it may take years to reach an adequate level of proficiency in simply being able to use the musical vocabulary of a style accurately, this is the first and least important step in the process of making beautiful music.

Once you’ve got your notes in order, it’s time to move on to all the other aspects of composition and improvisation such as dynamics, phrasing, form, motivic relations, etc. that make great music what it is.

So how did Beethoven’s music evolve over his career? Well, I recently read quite a few chunks of a book called “Inside Beethoven's quartets: history, interpretation, performance” by Lewis Lockwood and the Juilliard String Quartet. It helped me understand what was so amazing about Beethoven as well as how he became increasingly sophisticated over time. It had nothing to do with harmonic inventions. Beethoven was an architect. How bits of musical information interacted, how he played with form and structure, with dynamics and pacing, was what made him a master.

So why blessing? Well, for starters, check out Christos Hatzis’ essay called “The Crucible of Contemporary Music.” One thing he talks about is that when we start out as artists, we are, in all honestly, just following an egotistical desire for attention and affection. Over time, if you’re lucky, this urge to create can grow into something more mature, more mystical, and less self-centered.

So why the Beethoven Blessing? Beethoven understood better than any other composer had until that time that we would turn him into something he wasn’t: a caricature and a god. He was the first composer to take very seriously the idea that he was writing music for people who he would never meet, perhaps for off into the future. When people reacted negatively to his middle or late quartets, he responded that they were written for the future, for others who would be able to understand them better (I’d love to be more specific but I returned the book over a month ago and don’t feel like doing the research, but this fact is based on an anecdote told by Lewis Lockwood who is a serious Beethoven scholar). Beethoven had an ego. A big ego. You need one to do what he did. You have to believe yourself capable of great things before you stand a chance at doing them. It’s a struggle not to let that get to your head.

Although Beethoven’s deafness brought him great suffering and made him suicidal, in a way it was a blessing because it forced him to limit his artistic vision to a very specific set of criteria. If he had never gone deaf he might have simply tried to do too much, even with all his colossal talent. If he had never gone deaf, we would never have all the beautiful works that he could not have written unless he had gone deaf. And he might have spent too much time anticipating much of the harmonic innovations which would be developed over the following century and as a result not succeeded in being the pinnacle of structural genius of Western music.

Furthermore, Beethoven’s deafness is a blessing to the rest of us, because it teaches us how much goes into the art of composition and interpretation that is completely outside the mere selection of notes.

One afterthought while we’re on Beethoven, a post-script so to speak, is that I don’t agree with the notion of writing for the future. Music is about connecting to an audience. A live audience. Not necessarily a large audience. Not even necessarily an audience at all, just the simple sharing of music amongst musicians creating a moment together is a beautiful thing. Compositional tools which have no impact on a listener are completely unnecessary from the perspective of creating for an audience. That isn’t to say they must be completely abandoned. If they don’t detract from the piece of music emotionally at all, and they bring the composer satisfaction, no harm done. But if the composer’s intellectual satisfaction comes at the expense of the listener’s emotional satisfaction, than in a very real way the composition is a failure. I bring this up because, sometimes Beethoven is simply too long for me. I was surprised to find after listening to the quartet Op. 130 that not only was it extremely long, but it was long even though the Alban Berg quartet had actually left out many repeats in their performance. Of course, if a piece is written for musicians to perform simply for their own enjoyment in private, then the composer has met the goal of satisfying his audience and has succeeded even if most people won’t like it. Still it’s funny how so many jazz musician’s and classical composers resent the fact that their music is not appreciated by a wider audience yet they make no effort to accommodate and compromise with this audience. Every relationship is a two way street.

Friday, October 30, 2009

Thursday, October 22, 2009

One Way Road

Could this be done with whole or half notes and chords? Could we take a voicing and plane it up in whole or semi-tones, allowing ourselves to alter 1 or 2 notes by a semitone in either direction to compensate for the changing chord functions, all the while moving in a single direction up the fretboard for as long as possible? I think so. Definitely to be done with a bass player.

Monday, October 19, 2009

Ted Meets Mick

If I had generated so little new material while creating all the following studies, why was it that they all felt fresh and as if I was constantly coming up with new voicings? The answer is that I was recycling voicings, but not only in different keys, I was also changing their function. This strange voicing sounds bright on a Cmaj7 in All The Things You Are, but dark on Am(maj7) in Blue In Green.

This shouldn’t surprise me because I wrote and thought a lot about how this is the “green” way to use new material. Yet it wasn’t a point I had consciously set out to illustrate in the studies, however I recognize my following my own advice in hindsight.

So why Ted meets Mick? Well, if you’ve ever opened a Ted Greene book, you’ve been overwhelmed and quickly exhausted by the amount of material within. Nevertheless, something should be said for the systematic layout of the material using chord diagrams, not tabs or sheet music.

If you’ve opened up Mick Goodrick’s Voice-Leading Almanacs, then you also know that the same musical information can be applied and combined in ways with other information which no longer make it sound the same.

Seriously, have you ever tried cataloguing your knowledge? I just did, and I got an answer: 38 (plus probably another 30-40 voicings which I ignore because they’re very basic or I’ve been using them for a long time and know who they came from). It’s kind of liberating.

The Voice-Leading Almanac volume II is called “Don’t Name That Chord.” It deals with clusters and fourths which defy easy tonal categorization. But really, this is a good idea for any and all chord voicings we have. An Em7 is a Cmaj9 is a Am11 is a Dbm7(b9b5). So when I made my charts of all the interesting chords I’ve been experimenting with, I purposefully didn’t give them any names or write down what key I originally used them in or anything like that. All I’ve got is a bunch of ambiguous blobs on an undefined area of fretboard.

Now, my job is to take each of these chords and play with them. Rather than only deciding that a chord is a Cmaj7 and then going through all the songs where Maj7 chords are and using it there, I’m going to try and look at each voicing with an open mind. What could this voicing be? Could it also be a m7b5 voicing? Well, let me see where I can use it in that context. Let me see how I can take 38 and turn it into 380 without ever creating a genuinely new shape or intervallic structure.

However, if I were going to try and find new shapes, I think my next step, following in those of Mick Goodrick, would be to plane any and all of these shapes modally through major and melodic minor.

Sunday, October 18, 2009

An Intellectual Framework for Improvising

The lowest level of improvisation and musicianship, in my opinion, is finger-focused. In other words, the musician’s relationship with the instrument is very visual, and whether conscious or not, his understanding of what he is doing is very much about shapes. This musician can only play in exact fingerings and executing exact patterns which he has already practiced extensively. This is something we all need to do, so again I stress the word “only”. You can tell who these people are by asking them to play a passage and then repeat the same passage not even in a different area of the guitar, but even with a different fingering. They simply can’t do it. This is because their understanding of their actions is limited to the physical activity they execute with their hands. For them technique is not a means to an ends, but the experience itself of music making.

The next level of improvisation and musicianship, in my opinion, is someone who is conscious of the notes beneath their fingers and their corresponding sounds, but who focuses on technical virtuosity, requiring them to often be stuck in repetitive patterns. Their interaction with music is deeper than the first group of people, but their ability to interact meaningfully with other musicians is limited by their lack of control and ability to both listen and react to others.

The next level of improvisation and musicianship, in my opinion, is someone who can find a genuine balance between static virtuosity and listening/reacting to others in a controlled fashion. The problem with these musicians is that they do not practice enough. This lack of preparation forces them to place an unbalanced amount of concentration on their own actions rather than an equal amount of concentration on their sound as well as the sound of the other people they make music with. Not that they aren’t listening, but they could be listening better if they weren’t struggling to remember what to do as it was happening.

The highest level of improvisation and musicianship, in my opinion, is someone who has the technical freedom to create truly spontaneous music. While I’ve already spent time explaining that we can never create a new scale or chord shape on the fly but only rearrange preexisting patterns, these musicians derive their spontaneity from their ability to respond with a high degree of versatility, sensitivity, and freedom to the actions of the other musicians they play with. Because they are extremely well prepared to play, their reaction time is minimal and they have more awareness as to what other people are playing.

It should be noted that somewhere along the line we all probably oscillate between any and all of these descriptions, perhaps even within the same night or even within the same song.

I would also like to note that I’m fully aware of how subjective, personal and arbitrary this is and how everybody has the right to prescribe their own set of criteria and standards when evaluating a person’s competency.

I would also like to note that my degrees are ranked in order of expressiveness as I see it, with the person not who can play the fastest or anything like that, but the person who is most capable of freely expressing themselves on their instrument at the top. It is not the amount of material we are able to digest or the speed at which we can regurgitate it, but the meaning and emotionality of how it is implemented as well as our consciousness of what everybody else is doing.

I would also like to note that this scale refers to musicianship and improvisation. It would be silly to take what I’m saying out of that context. A singer-songwriter may only play five or six chords, may have no real understanding of harmony or the guitar, but this is not an essential skill for their mode of expression. Simply put, their skill as a musician is a secondary concern. They may not be very good musicians, and they may note have a clue how to improvise, but this is not the means they have chosen to convey their emotions and is an irrelevant criteria for judging their artistic merit.

Finally, I would like to note that among the two “highest” levels their is an ability to think of all the available notes in a scale when creating melodies, and to have the technical freedom to play any notes in any order they can think of and, tempo permitting (the faster the tempo the more linear any new idea will be), have the technical freedom to create spontaneously and play the new melody.

For instance, why practice playing a scale in series of intervals or triads or four note chords or any other pattern (some of which I have spent much time discussing)? Is it to play those patterns at wickedly fast speeds and wow people with your technical virtuosity? Or is it so that no matter where you are on the fretboard, and no matter what finger you are playing whichever note with, if the next note you want is a 4th, 5th, 6th, 7th, or anything else away, your fingers are prepared to play that note with a seemingly instant reflex? Not that there isn’t a time and place for mechanical and “prerecorded” sequences at high velocities. They are useful for creating transitional and exciting material. But is it more (or at the very least equally) about systematically playing through all the possibilities of which music can be made up?

Think of chemical and physical description of the world. The periodic table has 117 elements, but all these elements can be described as combination of protons, neutrons and electrons. And even these protons and neutrons can be broken up into smaller components. So all the known matter and physical events which take place in the universe can be reduced to the interactive relationships between a handful of forces on a handful of particles.

Music can be thought of in a similar light, so to speak. By taking our instruments and practicing musical material on them, not by practicing licks, but by practicing the very building blocks of all music, from serial music to Gregorian chant (intervals), we can react in the most free way possible.

DISCLAIMER: Principles of this article might seem to contradict in spirit the previous article. If spontaneity is an illusion, why then spend so much time talking about levels of spontaneity and the various degrees to which it can be achieved? Well, let’s think about it. If you play every interval possible on a guitar from every note to every other note, than no melody from that point on could ever be considered truly spontaneous because it is made up of tiny elements all of which you have already experienced. Furthermore if you take steps to consciously try not to spew out long and repetitive strings or sequences of these limited number of elements (much like DNA), than you are making fresher music. Certain small patterns of strings constantly reappear (arpeggios for instance) and this cannot be helped, but there are random mutations and variations that can also take place.

Definition of Improvising Revisited

Ironically, my first discussion (The Upward Spiral) was centered around the notion of closed position and working extensively on the interesting possibilities that can arise from an extended study of one position. I was thinking about how I could spend years working on that idea. Well I was definitely right on that one because I’ve abandoned the concept in my practice for the time being. That’s ok though, maybe I’ll pick it up again in the future. At the time I was playing rhythmically complex and harmonically simple modal music, so these were the kinds of ideas floating around. Now I’m back in school and reexamining some more standard jazz and tonal contexts and all those ideas just don’t seem very relevant right now. Still, they’ve definitely had their influence on the way I think of and hear single line solo and melodic construction.

So for the last month and a half, I’ve been working on building small studies using chords that were new to me over standard tunes, all of which are posted here, most of which have accompanying videos. Now I’m faced with a new problem, how to integrate dozens of new voicings into contexts outside of the ones I originally used them. Every song has voicings that arose from the colors and mood of that song’s harmonic progression and melody. How can I generalize this information so I can better use it in any situation and make it a working part of my vocabulary?

The answer is old and obvious. Isolate the information and then transpose it all into all 12 keys, perhaps choosing a voicing every day or week and forcing myself to use it in a variety of different tunes and keys. But I’m feeling a little philosophical, and I’d like to dive into what exactly I think happens to our minds when we go through that process.

I sometimes hear people say how they have trouble feeling spontaneous when playing jazz. Everything seems to be prerecorded and regurgitated not in the organic fashion described above, but in a way that seems contrived and unemotional. They wonder how they can take their playing to the next level. I always ask the same question: How do you feel when you take a rock solo in a music idiom you’re more used to, say rock or blues? They usually say that this is the kind of freedom and feeling that they wish they could attain within the context of jazz music. So already half the battle is won because we’re aware of the feeling we wish we could capture with our new vocabulary.

But how did we all get to this place as young guitarists within the simpler context of rock, usually modal or blues in nature? Well, my belief is that we simply waited. We all had to spend months and months, if not years, learning the positions of the modes and developing our technique. Did our solos feel organic back then? Did we feel at ease and in control over the sounds we made? Probably not. But now, five, ten, twenty years later, depending on how old we are, our fingers somehow “know” how to navigate seamlessly through the notes of a major or minor scale, and any musical idea we can think of, our two hands cooperate effectively to execute. The truth is, we simply forget doing the work, and that distance allows us to approach the structure of the scale with a freshness and freedom that seems to help us express what is deep inside.

So how do we get to a place where we feel at home and emotional in a musical scenario that is intellectual and perhaps complex? We wait patiently. Practicing is not the answer. It is a step in the process. But not practicing is also a step. We have to take the time to thoroughly learn whatever material we are struggling with, but also take time to let things sink in, to forget them, and then upon remembering them later on, to use them in a way which is more satisfying.

In other words: improvising is an illusion. Nothing we do is truly improvised. Only the passage of time and the chemistry of our consciousness allows us the feeling of spontaneity. That’s ok. It’s the feeling we’re after, not some abstract notion of absolute and distilled invention. Especially as the tempo we play at goes up, our ability to forge new patterns within preexisting patterns continually diminishes, but nonetheless we are left with the feeling that we are doing something new and exciting.

When I see Am7 written on a page, there are probably 10 chords that I do 95% of the time. But rearranging and combining those 10 things, as well as leading into and out of them in different ways, results in an infinite number of possibilities. I move to these chords and shapes by carefully forged instincts created through diligent practice. Once again, the excitement and meaning I experience when playing comes from not remembering the process of creating those very reflexes.

To sum up, jazz, much like composition, is the very experience of maturing itself.

Friday, October 16, 2009

Monday, September 7, 2009

Friday, September 4, 2009

Wednesday, September 2, 2009

Wednesday, August 19, 2009

Rhythmic Jigsaw Puzzle

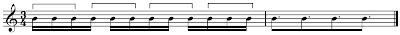

A combination of different inspirations has led me to a very specific rhythmic problem. I’ve been listening to a lot of recently composed classical music which is influenced by Indian rhythms. There is a lot of polyrhythms, of long beat cycles etc. One thing I’ve noticed is that typically we see the play of 8th notes grouped into 2s and 3s, we see triplets, and duplets, and we see things like a rhythmic pattern consisting of an odd number of subdivisions superimposed over another rhythmic figure consisting of an even number of subdivisions, causing one to feel displaced.

All these things are great compositional and improvisational tools, but they will serve us another purpose here. It’s hard sometimes to go into double time. But what about triple time? Mitch Haupers showed me a very useful exercise that involved a section of his book Factorial Rhythms dealing with rhythms in 6/4.

Using a metronome play what is written with the click representing the quarter note. Continue on to playing the 6/4 rhythm again with the click playing the half note. And then the third time the click will represent the dotted half note (triple time). This poses some interesting problems because the same rhythm may sound at one speed as 2 groups of 3 and at another speed as 3 groups of 2 which makes this especially disorienting.

Of course, it should be obvious in hindsight why Mitch very wisely chose to expose us to this kind of exercise using 6/4 rhythms. Look at how beautifully the rhythm fits into all 3 times. If he’d started with what I’m about to show you next, it would have been a little too much (hint).

What I’ve been seeing a lot of in the repertoire I’ve been studying and that seems like a natural extension of this exercise, is how to play 3/4 rhythms in the span of 2 or 4 beats,. What I haven’t been seeing is the MUCH harder problem of how to play 4/4 rhythms in the span of 3 beats.

Let’s start with 3 over 2 or 4. The division is actually quite simple. To divide 2 beats into 3 is a quarter note triplet. But to understand them more precisely we need 8th note triplets.

Now here’s where the real problem starts. These rhythms in themselves are easy enough to play with a bit of practice, but now we’re talking about superimposing rhythms over other rhythms. So let’s look at the tuplet as a structure over which we can hang a new pattern. This is going to become a more complicated polyrhythm because it is going to involve a full blown metric modulation superimposed over the original rhythm.

Let’s take putting 4 over 3 like I said we would. We need to divide the 3 beats into 16th notes, and then group those into 3s.

Now we get into a problem which could arise with the previous examples as well, come to think of it. As you can see, to superimpose 4 quarters in the space of 3 results in 4 dotted 8th notes. But what now if we wish to play a measure of 4/4 over a bar of 3/4. yikes! Now we’re going to have to have to use dotted 16th notes to represent the 8th note from the bar of 4/4.

The trouble, whether you try and think it through to exact mathematical values, or just feel your way through, is how to take something which you’re feeling as a natural division of 3 (such as the dotted 8th) and play a duplet over it (the dotted 16th). Now you have duplets which completely obscure where the original beat used to be, which is why we’re forced to write things out as they are in the middle of the 3 bars below.

It feels like we’re playing duplets in 12/8, and then superimposing THAT over 3/4. Ouch.

Friday, August 14, 2009

Staying Flexible

After looking back at everything I’ve written in the past 8 weeks or so, I’ve come to realize something: I’m not very good at sticking to an agenda. When I first sat down to create an agenda for the future based on the ideas from the Goodchord workshop, I had decided to focus on triads for a year, thinking horizontally, thinking in terms of a bunch of independent chord shapes, thinking harmonically. Very quickly though my interest became melodic, became vertical, and my mind began to wander into other territory harmonically. I still I think I can spend at least a year working on triads. After nearly two months, I can do the 4 patterns on only two modes out of the minimum of 10 or 12 I’ll need to learn them in for practical purposes. But I’m not where I set out to be. And that’s a great thing.

It’s happened to me when using the reference material of other authors and teachers that one of their ideas might inspire a concept or sound for me to pursue that was only indirectly related to their material. But I find this especially interesting now, as I try to create a body of reference material and interact with it as a practicing musician simultaneously.

Setting out to do one thing and accomplishing another is one of the beautiful things about playing music and one of the reasons we should never stop discovering things and growing as we practice. It was a nice idea to think of a hundred different variations on the triad exercise, or the nested serial intervallic sequences or whatever you want to call them (see “Oh Boy...” or “Spread it Around a.k.a. Serial Soloing”), but what good would it actually do me or anybody else reading those ideas to get totally bogged down in them and let them eclipse the kind of creative and fruitful, discovery oriented practice that we can and should all be doing more of. In five years, when I’ve mastered the triads and can play them to pieces and am looking for a warm up exercise that can also be a brainteaser, then maybe I’ll go back and look at some of that stuff. But in the meantime, the best thing I can do is to let go of that material, and not feel compelled or committed to sticking with it, even though I made it up with every intention of doing so.

And as for the horizontal triads, it turns out I don’t really even like them all that much (right now, at least), so why allow stubbornness to stifle me? In the end of the day, music should be an enjoyable activity and you don’t win any points for being right or wrong. I think we get preoccupied with being able to do things that are supposed to be really hard and being better than other people (you know it happens sometimes, it’s okay), instead of being focused on being creative and connecting with others in a meaningful way.

So let loose, don’t be stubborn, let the music flow, commit to the material that ignites your passion (tough luck if it happens to be material that takes a lot of prep-work) and don’t be afraid to change directions, keep it simple, be “bad” according to the person with the self-inflated ego trying to label you, and stay true to yourself.

Thursday, August 13, 2009

A Page From Mr. Goodchord

What do you do when you’ve discovered a new voicing you like? Well says Mick Goodrick, see if you can transpose it into the other modes of the scale. Lately I’ve been dealing with diminished and whole tone chords because these chords transpose very simply seeing as the fingerings don’t change.

What I have just come to realize, although it was right in front of my face the whole time in Mick Goodrick’s Voice-Leading Almanacs, was that like the diatonic D2&4 voicings in the major scale, all the voicings discussed previously can be converted into D2&3 and D2&4 with quite amazing results.

Monday, August 3, 2009

Sunday, August 2, 2009

Examples of Drop 2&4

Some nice drop 2&4 lines. Inspired by a chart by Mick Goodrick which lists all the different possible chords derived modally to play over the II V using melodic minor. (For more info on what different kind of chords there are check out the Voice-Leading Almanac.

Friday, July 31, 2009

Jaw-Dropping Arpeggios

For all that talk of drop 2 and 4 voicings, I really don’t know what to do with a lot of them. Unlike drop 2s, there is a much more limited range where they sound good. But starting to look at them in greater detail has reminded me of something I have meant to do for a long time and is certainly connected to the work I’m doing now in terms of creating more angular and jagged melodic textures.

I recently asked myself why I’ve been doing something for seven years and then decided to change it. This first thing I realized was that I always played consecutive triads voice-led melodically in the same direction and always the same inversion as a consequence. Well now I’m asking another question: why are my arpeggios always derived from closed position voicings?

An arpeggio is a chord except the notes are played individually. On a guitar we have very few closed position voicings that are convenient (and you can see many a guitarist sweep through them excessively on a Bbmaj7 or Gm7 chord). As a result, we tend to think of our arpeggios as derived from a scale because they often contain more than one note per string. This is also true but it doesn’t help us understand what’s about to come.

Once we understand that an arpeggio is just a different way to express a chord voicing, we can start to experiment with different chord voicings that involve greater leaps and inversions of chords.

Part of why this is so unintuitive and difficult to integrate into our playing is because these sounds are very difficult to sing, especially if we’re not the best singers. It appears that many people sing while they play because it makes them SEEM more expressive or in control of the sounds coming from their instrument, not because it actually MAKES them more expressive or in control. And there’s an inherent limitation to playing what we sing: we have to be able to sing everything we play. And as guitarists we are capable of doing things melodically which only a truly expert singer could ever even stand a chance of reproducing vocally, especially in tempo.

We put so much time into playing extensions, triads, and all sorts of stuff over our chords, but we always voice them in the way that is most singable to our terrible guitarist voices. Why not try and use a drop 2 voicing or drop 2&4 voicing as the basis for a melodic idea? Because we’re not good enough singers to sing three consecutive and large ascending intervals (i.e. 5th, 6th, 5th in the case of drop 2&4). But this is an interesting and modern sound! We should learn it and learn to hear it and understand it’s nuance but not ask ourselves to be able to sing it in any kind of performable way.

When we learn the lick we should play it slowly and sing each note, practice each interval, and be able to sing the lick at a very slow tempo or out of tempo. This is enough to be able to hear and appreciate the intervallic nuance of a line. So break out the inversions!

Wednesday, July 29, 2009

How slow Can You Go Pt. 3

So hopefully you’ve now tried all the different possibilities of placing a very slow metronome in various places in a bar, and even a shifting place within the bar. Maybe though, like myself, you really can’t do it very well. In fact, maybe, like myself, you’ve realized that you still aren’t half as good as you’d like to be at placing the click on the various offbeats, never mind alternating offbeats.

Enter Factorial Rhythm, another Goodchord publication by Mitch Haupers and Mick Goodrick. This is (not so) simply a book that breaks down rhythms into small 2 beat “seeds” or “cells” as they’re more commonly referred to, and then goes through all (or most or some) of the different possible permutations that can be created over 2 bars.

Here’s a small sample. There are 4 different ways to have two 8th note attacks over 2 beats of 4/4. This is all the possible combinations using all 4 seeds, beginning with a dotted quarter:

Now start with a single rhythm, and try and place the click on every downbeat and upbeat of the bar, swing and straight feel. Then move on to the other rhythms. Sticking with a single, short rhythm and moving the click helps you get over your tendency to push the click forwards or backwards onto a downbeat. You get used to the rhythmic dissonances in a very controlled environment.

Tuesday, July 28, 2009

And That's The Whole (Tone) Story

Oh yeah by the way, all I originally wanted to say was that a chord 1,3,#11,7, has only 2 voicings because of tritone substitution. And now replace the root with the 9th and enjoy all those inversions plus their various translations (I think that's the right geometrical term). And why Ab7 all of a sudden you might ask? Well I’m used to using these voicings the most in Stella so it’s a natural starting point. Of course it turns out all this applies to C in the end anyways...

Why does this chart have 2 lines when yesterday’s chart had 4? And now derivations of the derivations: